Intro of Book (download PDF of Intro)

Intro of Book (download PDF of Intro)This book is written in support of Dr. Maria Montessori’s own notion that movement is an essential factor in the physical and intellectual growth of children.

When mental development is under discussion, there are many who say, ‘How does movement come into it? We are talking about the mind.’ And when we think of intellectual activity, we always imagine people sitting still, motionless. But mental development must be connected with movement and be dependent on it. It is vital that educational theory and practice should be informed by this idea.

Montessori, 1967, p. 141

The purpose of this book is to provide Montessori teachers with ways to implement movement experiences for children in early childhood settings. Movement Matters is organized as a Montessori album with philosophy, methods, and lesson plans. Specific lessons are provided for presenting movement at the rug, for independent practice, and for large group physical activities. Lesson plans offer clear progressions and procedures for teaching fundamental movement skills and providing additional ways for movement practice.

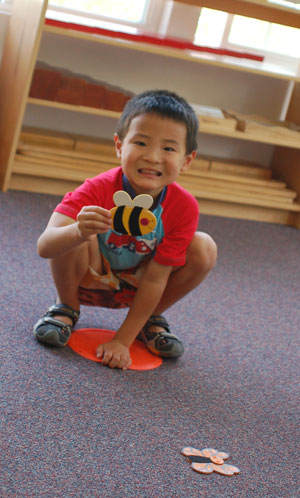

Most 2- to 6-year-old children are in the fundamental movement phase of motor development. They are also in the Sensitive Period for movement. The movement lessons in this album facilitate children’s acquisition of mature locomotor skills, object control skills, and stability, all of which are developmentally appropriate fundamental movements for young children. Through movement practice, the child further develops order, concentration, coordination, and independence.

The fundamental movement lessons and the large group physical activities in this book are considered structured physical activities. A structured physical activity has a specific purpose. It is an activity designed for a group of children that is planned and led by an informed adult. Structured physical activities have clear goals for physical development as well as supporting children’s learning of academic and social concepts. They give children repeated practice in fundamental movement skills, encourage positive peaceful play and improve children’s physical fitness through moderate to vigorous physical activity.

The fundamental movement lessons and the large group physical activities in this book are considered structured physical activities. A structured physical activity has a specific purpose. It is an activity designed for a group of children that is planned and led by an informed adult. Structured physical activities have clear goals for physical development as well as supporting children’s learning of academic and social concepts. They give children repeated practice in fundamental movement skills, encourage positive peaceful play and improve children’s physical fitness through moderate to vigorous physical activity.

In contrast to structured physical activities, unstructured physical activity is a child’s participation in free play, without direction. In free play, the adult oversees safety and peaceful resolution of conflict and encourages active play but does not lead the children’s play. Unstructured activities offer children opportunities to use their imaginations and to control and adjust their play choices with proximate adult supervision. These activities usually take place outdoors or in a designated indoor play space, typically during recess. Outdoor spaces can offer children opportunities to work with natural materials, build structures, or spend time in trees and low cover imagining a faraway place. Free play can be swinging and sliding on play equipment or climbing through a playhouse. It can be pushing and pulling toys, riding wheeled toys, or running around playing chase. In colder climates in winter, sledding, digging, and building snowmen become the focus. The opportunity for unstructured physical activity, which is just as important as structured physical activities for children’s development, is beyond the focus of this book.

Teachers may be unfamiliar with leading large groups of children in structured physical activities. Structure is provided – and normalization maintained – through the many repetitive management routines inherent in the fundamental movement lessons and within the additional ways to extend movement practice. Consistency with the routines and behavioral expectations are the keys to guiding all children through successful movement lessons, independent practice, and large group physical activities. When teachers maintain consistent expectations during structured movement practice, they give children the opportunity to build confidence and proficiency.

The fundamental movement lessons and the additional ways of extending movement practice found in this book have been presented effectively in Montessori classrooms. As explained in Chapter 3, movement can be presented in a Montessori classroom in a way that maintains normalization. The large group activities can be implemented in classrooms, gymnasiums, and indoor and outdoor play spaces. Fundamental movement lessons and large group activities require only simple, inexpensive equipment, and include specific ideas for modification to help teachers meet children’s varied developmental needs. The lessons and activities are easy to present, easy to learn, and the children’s participation is observably enthusiastic.

The fundamental movement lessons and the additional ways of extending movement practice found in this book have been presented effectively in Montessori classrooms. As explained in Chapter 3, movement can be presented in a Montessori classroom in a way that maintains normalization. The large group activities can be implemented in classrooms, gymnasiums, and indoor and outdoor play spaces. Fundamental movement lessons and large group activities require only simple, inexpensive equipment, and include specific ideas for modification to help teachers meet children’s varied developmental needs. The lessons and activities are easy to present, easy to learn, and the children’s participation is observably enthusiastic.

In addition to Montessori settings, the large group activities in this book have been taught with success in both center-based and family-based child care settings and could be modified to be successful in most any classroom. Teachers implementing movement in this way have a multitude of opportunities to observe and to develop a deeper understanding of motor development and its relationship to the overall wellbeing of each child.

Chapters 7, 8 and 9 contain the lesson plans for Fundamental Movement Skills. Included within these lesson plans are eight Locomotor Movement lessons, five Object Control lessons and three Stability lessons. These lessons take just a few minutes to present and can be taught in large or small groups at the large classroom rug.

We recommend teachers first present a fundamental movement lesson, followed by one or more of the three additional ways to implement that movement skill. These three ways are extensions of the fundamental movement lesson and can be implemented in any order. These three approaches to movement practice offer teachers instructional flexibility and provide varied opportunities for children to practice movements. Each of the three ways to implement movement is briefly introduced below and discussed in greater detail in Chapter 10.

1. Create a Movement Shelf. Teachers can place prepared, concrete, movement materials on the shelf for independent practice. Independent Works from the Movement Shelf offer children opportunities to independently practice movement skills. These materials are concrete extensions of concepts presented in the initial Fundamental Movement lessons or from the Large Group Activities.

2. Place a Locomotor Movement card into the Locomotor Movement card box. The movement cards can then be used to add movement to a child’s work cycle.

3. Play Large Group Activities in the classroom, gymnasium, or other safe, open play spaces.

Movement has great importance in mental development itself, provided that the action which occurs is connected with the mental activity going on.

Montessori, 1967, p. 142

As Montessori teachers, our job is to attend to the development of the child and provide opportunities for self-construction. The exercises and materials in a Montessori classroom provide opportunities needed to develop order, coordination, concentration and independence. We have faith that over time each child will develop self-control and positive behaviors, shaped through repetition of lessons. It is our belief and expectation that these experiences and opportunities for exploration will normalize every child.